Weaponizing The Masses: From Crowd Psychology Theory to Dystopian Totalitarian Oppression

This report will examine the origins, history, development, and eventual adoption of crowd psychology theories by authoritarian propagandists to booming businesses in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

In the winter of 2020, the entire world ground to a standstill threatened by a global pandemic. Fear, uncertainty, and skepticism gripped the globe as the COVID-19 virus rampaged across nations rich and poor. Faced with this existential threat, governments like the United States, spent millions of dollars to combat this virus on every front. The informational front became one of the most strategic areas of focus and contention. The government shifted gears and waged a massive informational campaign to raise awareness about the COVID-19 virus and to combat misinformation. The Center For Disease Control (CDC) launched various campaigns to influence the public to take necessary steps to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus, such as the “Crush COVID-19” campaign. The CDC promoted health education by focusing on the “four Ws”- “wearing a mask, watching our distance (social distancing), washing hands, and being wary of crowds” (Tolchinsky, 2020). Despite the government's best efforts, various individuals and organizations spread disinformation to the public. Taking advantage of the widespread fear, anger, confusion, and anxiety various groups used social media to spread conspiracy theories and disinformation about COVID-19 such as its origins, treatments lacking any scientific basis, and downplaying its severity. The informational war unfolded in front of everyday Americans becoming a common occurrence. Faced with this reality, many saw a new pandemic sweeping across the world; the virus of disinformation.

While the scale and speed of the spread of disinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic coupled with the rise of social media may seem unprecedented, in reality, it is not a new phenomenon. For hundreds of years, philosophers and psychologists have studied crowd psychology, attempting to understand why individuals are susceptible to persuasion and how political actors have leveraged this susceptibility to shape public sentiment to their will. Crowd psychology is defined as “the mental and emotional states and processes unique to individuals when they are members of street crowds, mobs, and other such collectives” (American Psychological Association, 2018a) From the writings of political philosopher, Niccolo Machiavelli in the 1500s to the birth of psychology in the 1800s, scholars have theorized about crowd psychology. However, it was not until the late 19th and 20th centuries that crowd psychology emerged as a formal area of study backed by scientific research. Pioneering theorists such as Gustave Le Bon and Wilfred Trotter developed influential hypotheses about crowd dynamics and the psychological elements that make mass persuasion possible. While these theorists wanted to share their ideas to better protect the public, unfortunately, their work would pave the way for one of the darkest chapters in human history. Early theories of crowd behavior were co-opted by authoritarian political actors, propagandists, and interest groups in the 19th and 20th centuries to manipulate public opinion and contribute to the rise of totalitarian ideologies that threatened liberal democracy.

The Italian peninsula during the 1500s was a patchwork of kingdoms, principalities, and feudal holdings. The democratic ideals of the Roman Republic were a thing of the distant past, feudal lords ruled over their land as paternal autocrats with immense power. The various small city-states clashed, and war was a common occurrence for the people of the Italian peninsula. It is within this context, that the philosopher Niccolo Machiavelli lived. Born to a wealthy family in 1469, Machiavelli had a career in Florentine politics as a bureaucrat. His first-hand experience as a politician and diplomat shaped his perspectives on political science, ultimately leading to his most famous literary work The Prince. Machiavelli argued that politics and ethics are completely separate and that if a ruler wants to maintain his power he must be willing to do whatever it takes regardless of morals.

(Photo Credit: Francesco and Raffaello Petrini, Palazzo Vecchio, Florence)

Machiavelli wrote extensively about how rulers can meticulously craft their persona and rhetoric to manipulate the perception of the masses. “...[A] prince ought to take care that he never lets anything slip from his lips that is not replete with the above-named five qualities, that he may appear to him who sees and hears him altogether merciful, faithful, humane, upright, and religious.” (Machiavelli, 1998) Machiavelli argues that the truth does not matter to the masses, what matters the most is perceptions. It is for this reason leaders should carefully choose how they present themselves and cultivate a persona of virtue despite how they may be in reality. Machiavelli also presents a cynical view of human nature believing that the masses are easily susceptible to deception. “...[I]t is necessary to know well how to disguise this characteristic, and to be a great pretender and dissembler; and men are so simple and so subject to present necessities, that he who seeks to deceive will always find someone who will allow himself to be deceived.” (Machiavelli, 1998) Machiavelli believed that a skilled speaker could easily sway the masses for their own will due to the naivete and present-mindedness of human nature. Machiavelli’s writings served as a practical guide for rulers to effectively wield power in their lands grounded in his personal experiences. Machiavelli’s theories would serve as a blueprint for generations of rulers preceding him. While his observations on rhetoric and public perception were immensely influential he does not explain why and how humans are so susceptible to deception. It would not be until the 19th century that scientifically minded psychologists would theorize about this aspect of human nature more in-depth.

The 17th and 18th centuries were marked by an immense intellectual and philosophical movement called the Age Of Enlightenment. Reason and critical thinking became the foundation for understanding the world around us. Many thinkers adopted empiricism, the belief that sensory experience should be our primary source of knowledge. This shifted theorists to take a more scientific approach to their thinking. By the 19th century, many theorists attempted to use empiricism to explain human behavior, including crowd psychology. Scottish journalist Charles Mackay wrote the book Memoirs Of Extraordinary Popular Delusions And The Madness Of Crowds in 1841. He explored the history of mass hysteria, manias, and crowd behavior by looking at different case studies throughout history. Mackay wanted to understand and explain why seemingly rational people could become swept up in irrational behavior when in groups. One such example he used to examine this was the prevalence of witch hunts throughout history. One reason why Mackay theorized that people partook in witch hunts was that they attributed their misfortunes to an external factor, in this case, witches. “...[T]he deaths from unknown diseases, which are often the consequences of their menaces, on the loss of the goods and chattels of your subjects, on the proofs of guilt continually afforded by the insensibility of the marks upon the accused” (MacKay, 2005). Mackay recognized that when people are suffering they sometimes resort to scapegoats to direct their frustrations. Fear coupled with the inability to have control over external circumstances affecting people leads them to seek explanations and something/someone to blame for their misfortunes. By blaming a scapegoat it can alleviate feelings of helplessness. Another important factor in crowd psychology is imitation and conforming to the group, which is explored by another influential theorist of the 19th century.

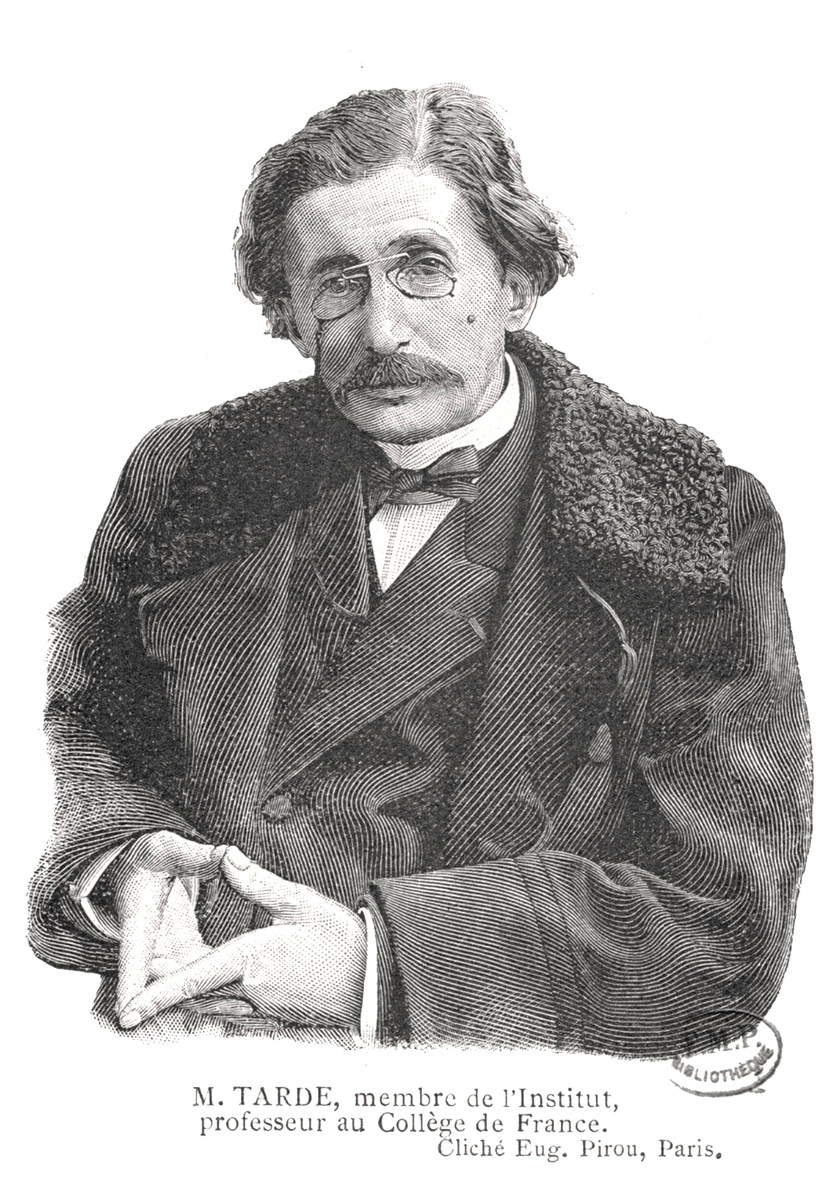

French sociologist, Gabriel Tarde sought to explain imitation and the shaping of individual behavior in his book The Laws Of Imitation published in 1890. Tarde believed that imitation was a fundamental aspect of social behavior. He theorized that inventions, discoveries, and ideas spread from person to person through imitation driving change in society. Tarde believed that ideas spread through imitation were contagious exponentially spreading from person to person. “And so likeness between artistic products is no proof at all of consanguinity, it points only to a contagion of imitation.” (Tarde, 1903). Tarde approached the concept of imitation from a scientific viewpoint. He argued that there were naturalistic laws of imitation similar to laws of physics. “There are three laws of imitation: (1) the law of close contact; (2) the law of imitation of superiors by inferiors; and (3) the law of insertion (where new behaviors either reinforce or replace customary ones).” (Merrill, 2017) The first law of imitation outlines that individuals close in physical proximity are more likely to observe and imitate each other's behavior. The second law states that there are imitators and models; imitation tends to flow downward from the model who is normally superior to the inferior imitator. For example, if a senior in high school wears his backpack with one strap in the hallway the younger freshmen will likely imitate that behavior. The third law states that new ideas or behaviors are either adopted alongside existing ones or overcome old ones and substitute them similar to natural selection in the theory of evolution.

(Photo Credit: Eugène Pirou/Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de santé)

From a crowd psychology standpoint, Tarde’s beliefs were extremely influential, especially in the realm of criminology. Tarde’s laws of imitation were applied to mob settings explaining why people were more likely to commit crimes when in a mob. Tarde’s first law of close contact explains that individuals near each other within a mob are more likely to adopt what the mob is doing, so if the mob starts to loot and burn stores the individuals in the mob are more likely to imitate that behavior. Additionally, if there is a leader or individuals perceived to be superior compared to the rest of the mob (those of a higher social standing) it is more likely that individuals in the mob will replicate their behavior. Also due to the contagious nature of imitation, the ideas and behaviors of the mob can spread quickly. Tarde essentially theorized about the psychological concept, closely associated with the work of later psychologist, Albert Bandura, known today as modeling. Tarde’s theories provided a framework for understanding how social influence worked within a crowd setting, explaining the dynamics of mob behavior and criminality. Like Bandura, Tarde emphasized the role of observational learning and the importance that role models have in influencing the behavior of others. Tarde’s theories about imitation were immensely influential at the time, however, they were limited in scope to just the criminal aspect of crowd psychology. One of Tarde’s contemporaries, heavily influenced by his work would go on to create one of the most influential literary works of crowd psychology to date.

French psychologist, Gustave Le Bon published his magnum opus, The Crowd: A Study Of The Popular Mind in 1895. Le Bon lived at the crossroads of tradition and modernity. The late 19th century was a crucible of societal, economic, and political change. Europe was amid rapid industrialization and because of this new classes in society began to form. Paired with the aristocracy of old were wealthy business tycoons and with the peasant farmers were the factory workers. Tensions soon arose as many flocked to the cities to work in factories and living conditions deteriorated. Class conflict became coupled with fierce nationalism and ethnic tensions. The multi-ethnic aristocratic empires of antiquity were showing signs of inherent dysfunction as the masses mobilized against the old order. Le Bon believed that civilization was at a turning point and that the ancient ideas that had persisted for hundreds of years in Europe were teetering on the edge of obsolescence. “While all our ancient beliefs are tottering and disappearing, while the old pillars of society are giving way one by one…The age we are about to enter will in truth be the ERA OF CROWDS.” (Le Bon, 1996) Le Bon is describing the beginning of mass politics, where political power shifted from being concentrated in the hands of a few elites at the top of society to the general population. No longer could the educated elites dictate how society should function, now politicians had to appeal to the masses which would express their beliefs as a crowd.

Le Bon theorized that specific psychological laws and criteria determined the characteristics of a crowd. “In its ordinary sense the word "crowd" means a gathering of individuals of whatever nationality, profession, or sex, and whatever be the chances that have brought them together. From the psychological point of view the expression "crowd" assumes quite a different signification. Under certain given circumstances, and only under those circumstances, an agglomeration of men presents new characteristics very different from those of the individuals composing it.” (Le Bon, 1996). Le Bon believed that crowds do not have to be physical gatherings of people but could also encompass entire nations given that the general population demonstrates the presence of the psychological characteristics of a crowd. When individuals become part of a crowd they lose characteristics specific to them, instead adopting common characteristics shared in the crowd, or what today we would refer to as groupthink. Le Bon believed that crowds were much more simplistic and emotionally driven compared to individuals thus enabling the crowd to be “extraordinarily criminal or heroic.” Le Bon viewed crowds as a singular entity and therefore identified some defining characteristics. Firstly, individuals present within a crowd lose their sense of individuality, adopting a sense of anonymity. This greatly reduces the individuals' feelings of responsibility and concern for social consequences. It is for this reason seemingly law-abiding individuals are capable of committing crimes such as looting, murder, and arson. Le Bon wrote, “An individual in a crowd is a grain of sand amid other grains of sand, which the wind stirs up at will.” (Le Bon, 1996). Emotions and behaviors also become contagious within a crowd, rapidly spreading and reducing the crowd’s ability to reason. When this occurs the crowd is swept up into collective action. For example, there is a group of sports fans celebrating their team’s victory in a championship. One fan from the rival team is angry and shouts at the group of fans; before there is time to think a violent brawl ensues. Under normal circumstances, a fight is less likely to break out between two individuals, however, in a crowd, the fans mobilize into action regardless of the consequences. Alongside losing their sense of individuality, people within a crowd conform to the dominant beliefs of the crowd. This leads to self-censorship and intolerance of those who are not a part of the crowd.

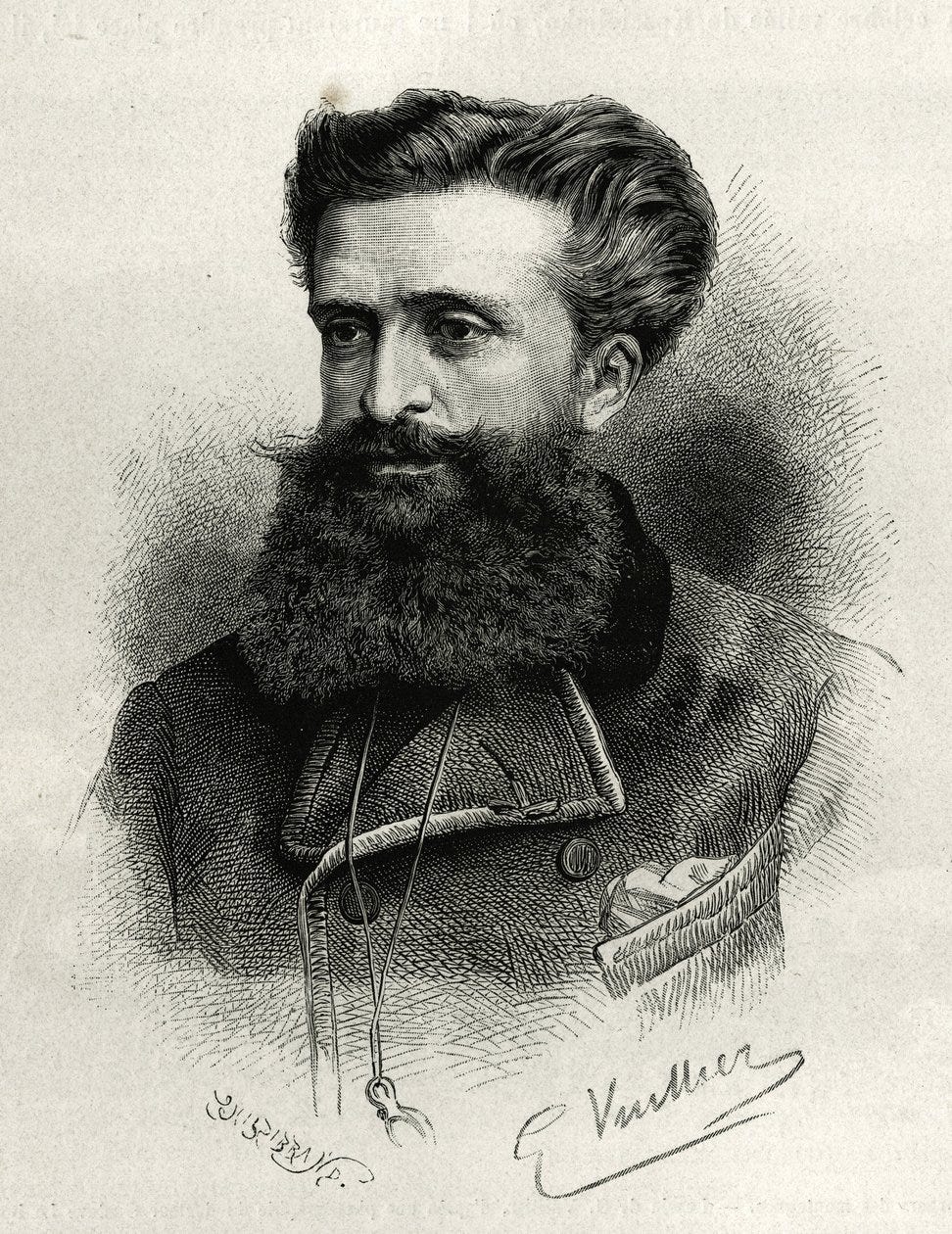

(Photo Credit: Gaston Vuillier)

Le Bon also suggested that individuals when present within a crowd become highly susceptible to influence. “The most careful observations seem to prove that an individual immerged for some length of time in a crowd in action soon finds himself…in a special state, which much resembles the state of fascination in which the hypnotized individual finds himself in the hands of the hypnotizer.” (Le Bon, 1996) The hypnotizer can mobilize a crowd to action. Similar to Machiavelli, Le Bon believed that the truth did not matter to the masses. A hypnotizer could sway a crowd easily by appealing to their emotions and telling them what they want to hear. “The masses have never thirsted after truth. They turn aside from evidence that is not to their taste, preferring to deify error, if error seduces them. Whoever can supply them with illusions is easily their master; whoever attempts to destroy their illusions is always their victim.” (Le Bon, 1996). So in this new era of mass politics, politicians had to simplify their messages with emotionally charged language to excite the crowds to gain their support. Le Bon identified certain traits that make people better hypnotizers. Charisma, persuasion, strong determination, and the ability to communicate concisely are paramount to guiding the crowd's emotions and actions. A strong leader serves as a focal point of the crowd where ideas and beliefs originate and can be organized. These leaders tend to be people of action, lacking foresight but are deeply convicted. Le Bon gives examples such as religious prophets, revolutionaries, and reformers. However, a strong leader is only one-half of what is necessary to sway the masses, the other vital half is the messaging.

Le Bon identified three principles that are vital in swaying a crowd. “The principal of them are three in number and clearly defined—affirmation, repetition, and contagion.” (Le Bon, 1996). In this case, Le Bon refers to affirmation as the act of asserting something is a fact without proof or reasoning. The example he uses is religious figures who assert that their doctrine and way of life are the holiest way to live life because God says so. However, affirmation is useless without the second principle: repetition. For an affirmation to be influential it must be repeated constantly. It is for this reason Le Bon suggests that simpler and more emotionally charged ideas are better as they can be easily repeated. After hearing an idea repeated over and over it slowly becomes truth in people’s minds regardless of reality. After an affirmation is constantly repeated and takes root in people’s minds, the last principle comes into play; contagion. At this point when people within the crowd believe the affirmation they will spread it themselves to those close to them (both physically and socially). Once the affirmation has spread throughout the crowd it becomes a “current of opinion” and becomes the dominant belief of the crowd. Those who do not believe it become the minority and are discriminated against. Le Bon’s ideas were immensely influential and studied by not only psychologists but also statesmen, propagandists, military officers, business owners, and more. Le Bon’s theories would soon be implemented shortly after he published his work as one of the most deadly wars in human history was lingering on the horizon.

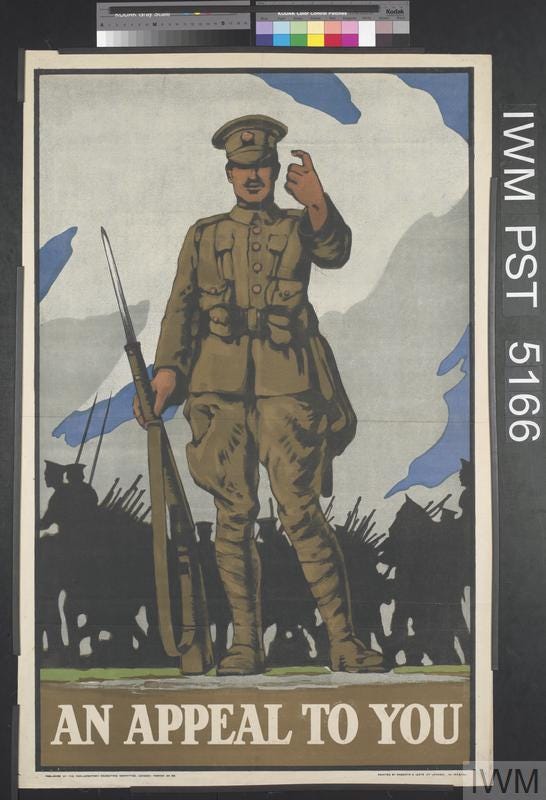

The First World War was a war, unlike any wars that came before it. The war encompassed the entire globe from Western Europe to the outer fringes of the Pacific Ocean. The First World War was the world’s first truly industrialized conflict with all of the advances of the Industrial Revolution; machine guns, modern artillery, chemical weapons, and tanks clashing with tactics and theories of the pre-industrial Napoleonic era. The industrial nature of the war coupled with mass politics meant that the lines between civilians and combatants became blurred. No longer were only kings and queens deciding the direction of the war; factory workers, farmers, and shipyard workers now had a direct impact on the war effort. The era of total war had begun. Total war is when the entirety of the resources of a nation, including its people are geared toward the war effort. Military strategists now began to theorize about striking the supply lines of soldiers from the factory floors to the shipping lanes of the oceans. While some theorized about direct strikes others sought to win the war through the informational front. If you could demoralize the enemy’s population while simultaneously indoctrinating your population with an iron will to contribute to the war effort any way they could, victory could be achieved. With that, the idea of propaganda was born. Propaganda is “a method of social control that attempts to strengthen or change the beliefs, attitudes, and actions of others by presenting highly biased information or sometimes disinformation.” (American Psychological Association, 2018b). Now for the first time in human history nations used organized propaganda, extending the war beyond the trenches to newspapers, and newsreels.

Wilfred Trotter was a British surgeon and a pioneer in the areas of neurosurgery and social psychology. At the height of the First World War, he published his book Instincts of the Herd in Peace and War in 1916. Building upon Le Bon’s work, Trotter analyzed crowd psychology from a biological perspective. Trotter argued that human behavior is not just driven by simple impulses like self-preservation and reproduction but also by a powerful innate herd instinct. This herd instinct motivates us to belong to groups and conform to their beliefs and norms. “...[T]he gregarious mental character is evident in man’s behaviour, not only in crowds and other circumstances of actual association, but also in his behaviour as an individual, however isolated…the only medium in which man’s mind can function satisfactorily is the herd.” (Trotter, 2016) Trotter believed that this herd instinct in humans was a powerful force both during times of peace and war. In war, it fuels national determination and the sense of a shared goal. Due to the powerful nature of the herd instinct, individuals are more likely to support the common cause even in the face of personal sacrifice. During peacetime, it can lead to conformity and hinder progress as minority ideas that challenge the collective beliefs of the herd are dismissed.

(Photo Credit: The Imperial War Museums)

Trotter argued that during war the emphasis on conforming to the herd leads to deindividualization and groupthink. “Expression, of course, has been found for the usual view that primitive instincts normally vestigial or dormant are aroused into activity by the stress of war, and that there is a process of rejuvenation of “lower” instincts at the expense of “higher.” All such views, apart from their theoretical unsoundness, are uninteresting because they are of no practical value.” (Trotter, 2016) Trotter believed that conforming to the herd comes at the expense of critical thinking and reasoning hindering strategic decision-making. Trotter also argued that the first nation in the war to break the other nation’s will to fight would win the war. He believed that Germany had more militaristic and nationalistic ideals meaning that the Germans relied upon aggression and swiftness more than the calculated and unified nature of the British. Trotter speculated that due to the aggressive nature of the Germans, they would be unable to win a protracted war as their morale would deteriorate as time went on due to their lack of unity. It is important to remember that Germany was a relatively new nation on the world stage at this time. Like the Italy of Machiavelli’s time, Germany too was a mess of overlapping principalities and kingdoms, until being unified by the kingdom of Prussia in 1871. Although unified into an empire, some local monarchs still retained power and influence over their people such as the king of Bavaria. Regionalism was very strong in Germany and besides Germans, there were also a considerable number of other minorities such as Poles, Danes, and the French. “If Germany was to be capable of a consistent aggressive external policy as a primary aim, the peculiarity of her circumstances rendered her unable to seek national inspiration by any development of the socialized type of instinctive response, because that method can produce the necessary moral power only through a true unity of its members, such as implies a moral, if not a material, equality among them.” (Trotter, 2016). On the other side of the ocean, an American statesman was not just theorizing about crowd psychology, but actively implementing its theories to impact the war effort.

George Creel was a politician, journalist, and writer who served as head of the Committee on Public Information (CPI), created after the United States entered the First World War in 1917. Creel published his work How We Advertised America: The First Telling of the Amazing Story of the Committee on Public Information that Carried the Gospel of Americanism to Every Corner of the Globe after the war in 1920. He detailed all of the specific actions the CPI took during the war, outlining which methods were effective in swaying public opinion both in the United States and overseas. At this point in the war, all of the warring nations had extensive propaganda campaigns and censorship of the media. Creel built on the other nations' experiences and Le Bon's writings to craft an expansive propaganda network that stretched the entirety of the globe. “Under the pressure of tremendous necessities, an organization grew that not only reached deep into every American community, but that carried to every corner of the civilized globe the full message of America's idealism, unselfishness, and indomitable purpose” (Creel, 1920). Creel recognized the importance of emotional appeals and made them central to all of the messaging of the CPI. He stirred up feelings of pride, fear, nationalism, and moral superiority when crafting his message about the United States. “What we had to have was no mere surface unity, but a passionate belief in the justice of America's cause that should weld the people of the United States into one white-hot mass instinct with fraternity, devotion, courage, and deathless determination” (Creel, 1920). Simultaneously Creel sought to dehumanize the enemy and highlight their supposed barbaric cruel nature. Creel also recognized that these powerful emotions could be evoked by using imagery. He limited propaganda to simple phrases that would be easy to read and remember with symbols and imagery. The many posters, pamphlets, cartoons, symbols, and films had similar visual cues and central themes stressing the importance of repetition. The iconic “Uncle Sam Wants You!” poster became the most recognizable example of this.

(Photo Credit: James Montgomery Flagg | NARA)

Creel was one of the first propagandists in history to take advantage of cinematography. “Through the medium of the motion picture, America's war progress, as well as the meanings and purposes of democracy, were carried to every community in the United States and every corner of the world.” (Creel, 1920). Alongside visual imagery Creel also implemented the “four-minute men.” These were persuasive public speakers who would give fiery patriotic speeches to large crowds of people in four minutes or less. The CPI understood that at this time the average person was not well educated so the use of auditory and visual methods was far more effective compared to lengthy articles in the newspaper. The CPI also recognized that the United States was a patchwork of various immigrant communities, so it translated all of its propaganda works into a wide variety of languages. This served two purposes; to influence immigrant communities in the United States and to distribute that same propaganda overseas to neutral nations to sway them to align closer with the Entente, allied nations to boost morale, and enemy nations to break their will to fight. “[A] triple task confronted us. First, there were the peoples of the Allied nations that had to be fired by the magnitude of the American effort and the certainty of speedy and effective aid, in order to relieve the war-weariness of the civilian population and also to fan the enthusiasm of the firing line to new flame. Second, we had to carry the truth to the neutral nations, poisoned by German lies; and third, we had to get the ideals of America, the determination of America, and the invincibility of America into the Central Powers.” (Creel, 1920) Of course, there were dissenters to the war effort and Creel made sure to use the CPI to crack down on any voices opposing the war effort.

The Sedition Act of 1918, alongside the Espionage Act and the CPI’s influence over the media, ensured that any opposing voices were shut down. Creel used voluntary patrols that would identify and report those who held anti-war sentiments. The CPI realized that openly implementing censorship would hurt the government’s appearance so rather than supporting a censorship bill, the CPI would rebrand the concept of censorship. “My proposition, in lieu of the proposed law, was a voluntary agreement that would make every paper in the land its own censor…” (Creel, 1920) Creel understood the importance of public appearances, similar to what Machiavelli wrote regarding how leaders should present themselves to their people. Creel’s work as leader of the CPI would extend beyond the First World War providing propagandists with a textbook guide on how to sway public opinion. Businesses recognized the vast potential of Creel’s methods and would implement them not to sway public opinion to fight a war but to buy their products, initiating a new era in marketing and advertising.

(Photo Credit: Marina Amaral)

Edward Bernays most commonly referred to as “the father of public relations” worked alongside Creel on the CPI. Therefore he was heavily influenced by Creel’s work and wrote extensively about the use of propaganda and the importance of public relations. He published his most important work Propaganda in 1928. Bernays used his experience on the CPI coupled with literature from psychology (such as Le Bon, Trotter, and Sigmund Freud) to determine the best public communications techniques. Freud’s discovery of the unconscious mind became fundamental to Bernays’ view on public relations. Bernays believed that companies could tap into the unconscious minds of consumers to subtly convince them to buy their products. Bernays’ work was instrumental for businesses across the United States. Due to Bernays’ work, the United States and later the entire world had a marketing revolution and Bernays is in part, responsible for the massive consumer culture we see today in the United States.

At the time in the 1920s, it was considered to be taboo for women to smoke cigarettes. If tobacco companies could somehow convince women to smoke, they could double their profits. Edward Bernays orchestrated an influential public relations campaign that sought to achieve that very goal. Bernays linked the concept of smoking cigarettes to the budding women’s liberation movement by pairing the idea of women smoking cigarettes with the symbolism of challenging traditional gender norms. Bernays relied heavily on emotionally charged messaging such as women’s fear of being continuously oppressed by men. He would stage women at key events to light up and smoke cigarettes encouraging other women in the crowd to do so as well. The most famous example of this was in 1929, “... Bernays encouraged women to march down Fifth Avenue during the Easter parade in New York City and protest against gender inequality. Bernays telegrammed thirty debutantes from a friend at Vogue to participate in the demonstration, encouraging them to combat the prejudice against women smokers.” (McCutcheon, n.d.) Bernays strategic use of the power of the media was also paramount to the success of this campaign.

(Photo Credit: PRINT Magazine)

Bernays ensured that photographers would capture the moment when carefully hand-picked women lit up cigarettes at the parade. These pictures would be circulated throughout the media giving off the impression that cigarette usage was more widespread than what it truly was with women. Along with reiterating the ideas of other crowd psychologists Bernays also repackaged those ideas in a way that was applicable to businesses. “He buys a certain railroad stock because it was in the headlines yesterday and hence is the one which comes most prominently to his mind; because he has a pleasant recollection of a good dinner on one of its fast trains; because it has a liberal labor policy, a reputation for honesty; because he has been told that J. P. Morgan owns some of its shares.” (Bernays, 1928) Bernays emphasized the key factors in public opinion for companies; the perceptions of the masses, constant advertising of the company so the public instantly thinks of that specific company, reputation, and simple positively emotionally linked imagery. While the use of these techniques by companies can be considered immoral and unethical, when implemented by totalitarian regimes the outcome becomes without a doubt dystopian.

The transformative nature of the late 19th and early 20th centuries made the creation of mass political ideologies possible. Karl Marx’s communism emerged as a response to the rapid industrialization and social upheaval of the 19th century. The new era of mass politics became a core feature of Karl Marx’s communism. Marx envisioned a political-economic system in which the proletariat (the masses) seized the means of production from the industrial elites, creating a classless society in which the masses of workers were the ones to determine the value of their labor. Marx understood that his ideology had to galvanize the masses to band together and mobilize as a unified force to be successful. Communists throughout Europe would agitate the masses by spreading propaganda that portrayed the world in simplistic emotional terms. The masses were made to feel oppressed, angry, fearful, and just in their morally superior cause. The emotions of the industrial workers were directed toward their enemy the bourgeoisie (industrial tycoons). The First World War was the destabilizing force needed in the world to provide a fertile ground for revolutionary movements to gain momentum. During the height of the First World War, the first communist state would come into being in the least likely place; agricultural Imperial Russia.

With the help of the Germans, exiled communist leader Vladimir Lenin, was able to capitalize on widespread discontent in the Russian Empire, spreading communist propaganda. Seizing the opportunity in 1917, Lenin and his Soviet supporters overthrew the provisional democratic republic plunging the lands of Eastern Europe into a complex web of civil and intrastate conflict. The Bolsheviks knew that the people's support was key to their revolution's survival. Almost immediately after seizing power, the Bolsheviks implemented state control over the media and all forms of public communication. “The establishment of Pravda was one of the first tasks [Lenin] undertook when he came into power. Pravda achieved the goals of Bolshevik propaganda by motivating the people and controlling the media available to them (Cole, 675).” (GCSE Modern World History, 2009). The Soviets introduced propaganda to every single aspect of the lives of the peasants. They made extensive use of posters, pamphlets, and even film. The Soviets established the first professional film school in the world. “The Vsesoyuznyi Gosudarstvenyi Institut Kinematografii (VGIK; “All-Union State Institute of Cinematography”) was the first such school in the world. Initially, it trained people in the production of agitki; existing newsreels re-edited for the purpose of agitation and propaganda (agitprop).” (Sklar, 2024) Although the Soviet Union was ideologically opposed to the United States in every way, they employed similar tactics to George Creel’s CPI, demonstrating that crowd psychology tactics supersede ideology. While the Soviet Union under Lenin was no doubt an authoritarian state, under Stalin it truly evolved into a totalitarian police state.

When Joseph Stalin took control of the Soviet Union he won a power struggle within the inner circles of the communist party. Stalin defeated his political opponents, leaving himself as the sole inheritor of Lenin’s Soviet empire. Not only did he continue to centralize state control as Lenin did, but he also implemented policies eerily reminiscent of the old tsars of Russia. Under Stalin, the state intelligence agency, the NKDV asserted dominance in all aspects of life. Secret police roamed the Soviet Union in search of opposition to arrest and send to Siberian prison camps known as Gulags. Now that Stalin defeated all of his political foes just one remained; the Soviet people. Stalin waged a war on the minds of the Soviet people; he crushed internal opposition to his collectivist policies and russified the Soviet Union; crushing any nationalistic hopes for autonomy. Forcing the disparate peoples of the lands of the former Russian Empire to adopt Russian culture and language, enabled Stalin to better unify these peoples into the new Soviet citizen, one that was loyal to Stalin and the new communist order. Stalin’s main weapon against the Soviet people would be a constant and steady stream of propaganda.

(Photo Credit: FINE ART IMAGES/HERITAGE IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES)

Propaganda seeped its way into every aspect of Soviet life. From artwork to education to architecture, everything was designed with the foremost objective of indoctrination. “This dicey balance of oppression and emotional fervor necessitated the development of a total propaganda, in which virtually every area of state and individual activity was under Soviet influence.” (Dome, n.d.). The religion of Imperial Russia was soon replaced by the state-sponsored deification of Marx, Engels (the founders of communism as an ideology), Lenin, and of course above all Lenin’s and Marx’s most devout follower, Stalin. Within every house, school, and public building the photo of Stalin had to be present. Stalin became the red tsar with a heart of steel. “The Bolsheviks put all their efforts into an attempt to monopolize all channels of influence, welding them together into a single, official channel. The regime successfully managed to turn schools and the mass media into organs of propaganda, and attempted, although with a lesser degree of success, to supplant family and church with government-inspired institutions.” (Dome, n.d.). The propaganda of the Soviet Union under Stalin was used as a tool to guide the masses toward whatever objective Stalin was pursuing at the time. For example, during his five-year plan, he envisioned a heavily industrialized Soviet Union that could challenge the other nations of the world on its own. To achieve this rapid industrial plan Soviet society had to be completely and violently transformed from an agricultural to an industrial society. Therefore, propaganda at the time heavily focused on the monumental achievements of Soviet engineering, the heroic qualities of the factory workers, and the selfless sacrifice of the laborers.

However, the state apparatus of the propaganda machine was also wielded as a weapon of repression. “A venomous propaganda campaign was employed against all those whom Stalin's regime considered alien and hostile to the new socialist order. Stalin singled out the richer peasants, labeled kulaks, as class enemies and stripped them of their homes and possessions, shooting those who resisted and deporting millions to Siberia…” (Dome, n.d.). Again Stalin used the vast propaganda machine of the Soviet Union as a weapon against his enemies or suspected enemies during the Great Purge of the 1930s. Stalin went as far as “disappearing” dissidents by having all mentions of them scrubbed from Soviet society. Even photos of them were edited and republished to have them removed. The most infamous example was the removal of the NKVD’s former head, Nikolai Yezhov from all records. “Defense Commissar Kliment Voroshilov and Premier Vyacheslav Molotov stroll along the Moscow-Volga canal with Comrade Stalin and NKVD (secret police) boss Nikolai Yezhov, who was arrested and executed in 1939. According to the retouched photo, Yezhov never existed.” (Conquest, 1998). After the violent five-year plan and the purges of the 1930s, the propaganda machine yet again was used as a weapon, this time against the fascist invaders during the Great Patriotic War (The Second World War). “The Soviet leadership realized that to survive, it would need to unite on a national front rather than an ideological one. Once again, propaganda was called to transform the values, attitudes, and behavior deemed necessary to mobilize the population in the interests of the state” (Dome, n.d.). Soviet citizens, imbued with complete devotion to Stalin and Mother Russia sacrificed dearly in the name of destroying the fascist pigs. Both Soviet and Axis propaganda dehumanized the enemy enabling its soldiers to commit egregious tit-for-tat crimes upon anyone; soldier or civilian that were unfortunate enough to cross their paths.

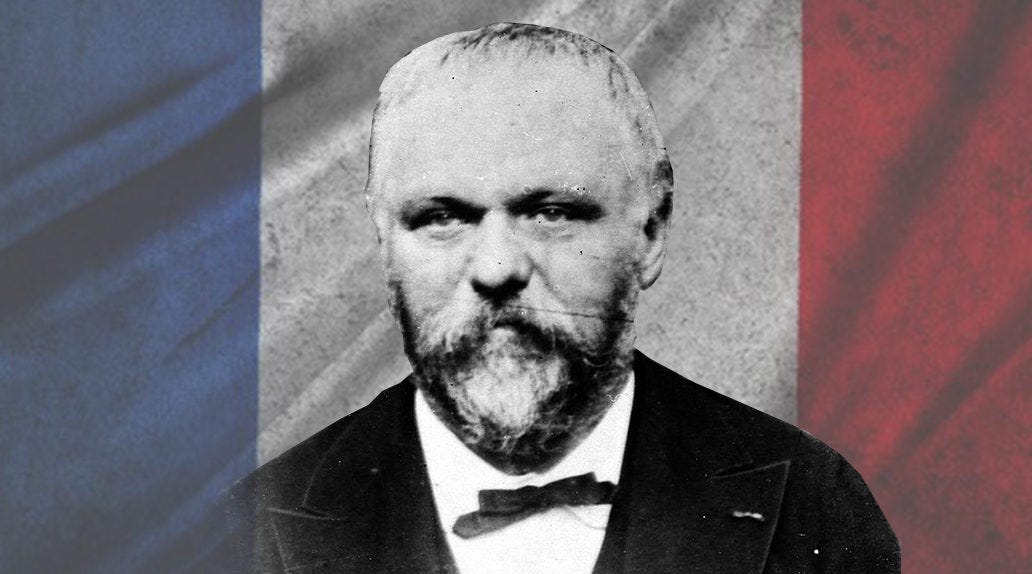

Karl Marx’s communism went on to develop into two major paths. The first path was from Marx to Lenin to Stalin as previously discussed. The other path developed from Marx to Georges Sorel to Benito Mussolini. Georges Sorel was a French socialist thinker and political writer who would go on to develop his syndicalist ideology called Sorelianism. Sorel disagreed with Marx’s worldview believing that it too narrowly interpreted the world through class divisions and economics. Sorel incorporated sociology and Le Bon’s work into his book, Reflections on Violence, which outlined his political philosophy. Sorel believed that there needed to be something else to galvanize the masses and rally them to the revolutionary cause. Sorel believed that myths were needed to act as a central idea that the masses could rally around. “..[M]yths, in which are found all the strongest inclinations of a people, of a party or of a class, inclinations which recur to the mind with the insistence of instincts in all the circumstances of life…” (Sorel, 1999). Myths which Sorel believed, were ideas that inspired the masses and would be held above any criticism. Sorel chose to elevate the myth of strikes to legendary proportions.

(Photo Credit: Lionel Baland - Elements / Eurolibertes)

At the turn of the 20th century, another ideology began to take root in the masses. This ideology, while seemingly to be the complete polar opposite of communism has the same ideological root, stemming from Karl Marx’s writings. The new third way; Fascism and at the head of this ideology was quite the complex man, Benito Mussolini. Mussolini was heavily inspired by the writings of Georges Sorel and Gustave Le Bon. Mussolini agreed with Le Bon’s belief in the transformative nature of mass politics in the world. “If the 19th century was the century of the individual (liberalism implies individualism) we are free to believe that this is the “collective” century, and therefore the century of the State.” (Mussolini, 1932). Mussolini believed that those who were not thinking in terms of collectivism (mass politics) would be left behind in the 20th century. In this regard, Mussolini agreed with Karl Marx and more so with one of his successors.

Mussolini like Sorel was disillusioned with the Marxist orthodoxy. Mussolini believed that while the Marxists rightfully tapped into the power of the masses, they focused entirely too much on the international aspect of communism. Mussolini believed that the inherent divisiveness of communism coupled with its dogmatic nature doomed the ideology to fail. “I saw that internationalism was crumbling. The unit of loyalty was too large… It was necessary to imagine a wholly new political conception, adequate to the living reality of the twentieth century, overcoming at the same time the ideological worship of liberalism… and finally the violently Utopian spirit of Bolshevism.” (Mussolini, 1970) Instead, Mussolini developed his ideology called Fascism, which took its name from the Roman term fasces, which meant a bundle of sticks. Mussolini viewed each syndicate, or self-organizing group of companies, unions, or individuals in Italy as a stick, and when they came together they formed an unbreakable bundle or the Italian word, fasci. Mussolini would use Sorel’s theory about myths to craft his myth surrounding the Italian people.

At this point in history, in the 1910s, Italy was a new nation and the idea of being Italian had yet to quite exist. The Italian peninsula was divided into various kingdoms, city-states, and principalities for hundreds of years. The Italic people identified more with their regions, towns, and even villages as opposed to the vague idea of “Italianess”. Due to the rugged terrain of Italy, culture and even language varied wildly from region to region. Mussolini believed that for Italy to be strong he first had to unite the Italian people. “We created our own myth. The myth is a faith, it is a passion. It doesn't have to be a reality. It is a reality in the fact that it is a goad, that it is a hope, that it is faith, that it is courage. Our myth is the Nation, our myth is the greatness of the Nation! And we subordinate everything else to this myth…” (Mussolini, 1922) Nationalism would become the core mobilizing factor of Fascism.

Italian nationalism went beyond simple patriotism, Mussolini invoked an almost spiritual worship of the Italian people and country. Giovanni Gentile, one of Italy’s leading academics, also known as the “Philosopher of Fascism” summed it up the best in his work The Origins And Doctrine Of Fascism. “ History is not a past that is of interest only to the erudite—it is present, alive, in the soul of us all. Those who are Italians feel themselves a part of this Italy. They find themselves not only in the blue of its sky, in its hills and its water, nor only in the desolate or mountainous land that alternates with its fruitful plains and its smiling gardens. We close our eyes, let us make abstraction from the horizons of its landscapes so varied in beauty and light—and Italy remains in our soul…” (Gentile, 2002). This poetic language, central to the doctrine of Fascism gave off an almost heavenly beauty to Italy, aiding Italians in directly identifying with the land of Italy, rather than their local cultures. However, to rally the Italian people to this myth, Mussolini and his Fascists had to rely heavily upon the psychology of mass percussion and propaganda.

Mussolini structured the Fascist movement in Italy around his heavily militarized, disciplined, and obedient paramilitary forces called the Blackshirts. United in ideology and numbers the Blackshirts acted as a single unit, with Mussolini at the head shaping their thoughts and behaviors as a skilled orator. The Blackshirts being Mussolini’s weapon were unleashed upon his thousands of opponents and the people of Italy. Through the violent oppression of the Blackshirts, Mussolini desensitized the Italian people to violence. When confronted for their brutal violent actions, Mussolini and his Blackshirts responded with their signature phrase “Me Ne Frego” or I do not give a damn. “Giovanni Amendola, the leader of the Italian liberals who published piece after piece and speech after speech condemning the deeds of Mussolini and his black uniform faceless mass… lies in his office (battered and bloodied). People call for the black mass and Mussolini to be held to account. Mussolini walks into the Italian parliament and takes the speaker's podium… he opens his mouth (and) the crowd of accusers goes silent. [H]e says “Yes I did it” and the crowd simply responds with “Me Ne Frego” as a black mass engulfs them all.” (Kraut, 2018). Through Mussolini’s calculated and strategic use of the Blackshirts, he normalized violence as a part of the political process, enabling the masses to become complacent to Mussolini’s actions, and paving the way for Mussolini’s rise as Italy’s dictator. Mussolini’s use of the Blackshirts is a perfect case study of the actual implementation of the theories of Le Bon and Tarde.

(Photo Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Unknown Provenance)

Mussolini also relied heavily upon Le Bon’s theories in shaping the Italian people’s psyche to be subordinated to the Fascist state. Similar to Stalin, Mussolini developed a totalitarian state that had a monopoly on information. Mussolini’s face was seen everywhere in Italy, from school classrooms to sculptures carved out into the sides of government buildings in Rome. His ideology infected all parts of Italian life; music, art, architecture, film, education, and the news; everything was dominated by Fascist messaging. Mussolini evoked strong emotions when speaking to the myth of the Italian people. He would say anything that would bring about the greatness of the nation. He used emotionally charged and passionate language when describing himself. For example, he said, “I am desperately Italian.” (Mussolini, 1970). Mussolini was also one of the first leaders to recognize the influence of famous Hollywood actors on the people. For instance, Italian-American film superstar, Rudolph Valentino would become an instrument of Mussolini’s propaganda.

Valentino would escape poverty in Italy emigrating to New York in 1913. Valentino’s astonishing looks and charisma would eventually enable him to rise to superstar fame in Hollywood. He starred in films such as The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and The Sheik. Valentino became a household name, known as the “Latin Lover”. Women across the world became weak in the knees just from hearing his name be spoken. However, just shortly after rising to superstar fame, he tragically died from perforated intestinal ulcers. This rare condition would become known in medicine as Valentino Syndrome. Valentino had a special place in the hearts of people across the world and his death was mourned by hundreds of thousands of people. As an Italian, Valentino also had a special place in the heart of Mussolini. “Acutely aware of the commotion that Valentino’s death will create and the interest it will spark worldwide Mussolini wants some of the spotlight to reflect on him. He sends an honor guard of four Blackshirts to stand at attention as the dead superstar lies in wake in New York. Well, in reality, it’s four local actors hired by the funeral home and dressed up as Blackshirts, but in the world of make-believe and propaganda that hardly matters - the message is clear - Mussolini loves Valentino and then Valentino must have loved Mussolini, right?” (Olson & Kapteijns, 2019). Mussolini used this event to strengthen Italian nationalism, demonstrating that the Italians of the world were united regardless of where they lived and that the achievements of Italians would reflect not upon the individual but on the Italian people as a whole. Mussolini took full advantage of the technological innovations of the 20th century. Radio and film became instrumental in maintaining his grip on power and his popularity abroad. Mussolini, the father of Fascism, would inspire fascist movements and leaders throughout the tumultuous interwar period. One such admirer would go down in human history as one of the most infamous and evil human beings to walk this earth.

Following her defeat in the Great War, Germany was completely transformed. The German Empire was dissolved and many of its lands were stripped away. What took the place of the empire, was a weak unstable squabbling parliamentary democracy. From the onset, the new Weimar Republic was beset by revolutionary radicalism and violent reactionism. Additionally, the economic foundation of the nation was fraught with structural issues, such as hyperinflation, and massive unemployment creating widespread social unrest. While the German economy would recover eventually leading to the Goldene Zwanziger Jahre or the Golden Twenties, it would be better to describe this time as the Golden Plated Twenties due to the German economy’s reliance on cheap American loans. The economy was a delicate house of cards and all it would take was one blow to have it all crash down. This is what happened in 1929 when the stock market on Wall Street collapsed. It is this unstable environment that created the perfect storm for the rise of a uniquely German brand of fascism; the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or the National Socialist German Workers' Party better known as the Nazis.

(Photo Credit: Mary Evans Prints Online )

The party’s leader, Adolf Hitler embodied all of the traits that Le Bon attributed to the ideal hypnotizer. He was charismatic, passionate, an excellent public speaker, and a man of action. His fiery speeches attracted thousands to his cause, including Joseph Goebbels, a master orator and propagandist, who specifically studied the works of theorists such as Le Bon. Together, Hitler and Goebbels would use many of the aforementioned theories and influences discussed to seize power and the minds of the German people masterfully. Hitler like Mussolini, was influenced by socialist thought and he even recognized Marxism for correctly tapping into the political power of the masses. “Social Democracy and the whole Marxist movement were particularly qualified to attract the great masses of the nation, because of the uniformity of the public to which they addressed their appeal.” (Hitler, 1939). However, similar to Mussolini, Hitler recognized that Marxism was too rigid and divisive, so he sought out a different way to unite the masses besides class conflict.

Hitler capitalized upon two myths to unite the German people. The first one was the so-called stab in the back myth. At the time, the idea that Germany did not lose the First World War militarily, but was instead betrayed by a corrupt cabal of civilian politicians and the wealthy elite spread like wildfire throughout Germany. Hitler was a strong proponent of spreading this myth, capitalizing on the widespread feelings of shame, anger, and dissatisfaction with the new liberal democratic government. Hitler injected his own anti-Semitic beliefs into this myth, claiming that there was an international conspiracy by the Jews to oppress the German people. This gave the Nazis a clear target to blame all of Germany’s problems on. The Nazis were united in their hatred for the Jews and through their shared enemy they found strength. “The man who is not opposed and vilified and slandered in the Jewish Press is not a staunch German and not a true National Socialist.” (Hitler, 1939). Hitler’s second myth was the idea of the so-called Aryan race. Hitler argued that the German people or Volk were descendants of a master race. Therefore the Germans were superior to all other races that were corrupted throughout history by mixing with so-called “inferior races.” Hiter’s idea of nationalism was much more rigid compared to Mussolini’s. Mussolini believed that Italian culture was what defined the Italian people, not strictly ethnicity. Like the Romans Mussolini believed if he could assimilate the people under his control into a common Italian culture, he could make them Italian, uniting the fairer-skinned Northern Italians with the more Mediterranean Southern Italians. Hitler on the other hand believed that the German nation was not defined by borders or a common culture but rather by blood. Therefore not all those living in the German borders shared German blood, justifying the targetting of Jewish people living in Germany and the expansion of the German state to incorporate lands that ethnic Germans lived on. This idea of a shared bond through blood was a powerful motivator in building a sense of unity for the German people that transcended nationalism.

Another important factor in Nazi ideology was the total embodiment of the ideology and the projection of maximum strength. “The psyche of the broad masses is accessible only to what is strong and uncompromising.” (Hitler, 1939). The Nazis had an almost incessant obsession with social Darwinism believing that they were superior because they were the strongest. This idea of natural strength especially resonated with rural and disenfranchised Germans who rallied to the Nazi cause with hopes of returning to supposed greatness. This idea of supposed greatness and a romanticization of the past is another hallmark aspect of Fascism and Nazism. In this way the Nazis were extremely reactionary, championing “traditional values.” “ ..[T]he institute (the Institute For Sexual Science in Berlin) is raided by storm troops who take as many books as they can carry and bring them to Opera Square. They are stacked in a heap and set ablaze. Around 10,000 books are burned. The press is jubilant reporting on the destruction of a poison shop run by Jews hell-bent on destroying the German family.” (Olson & Deinhard, 2019) The Nazis attributed Germany’s misfortunes to the rapid moral degradation found in cities. They blamed liberal democracy and the Jews for this of course. While Nazi ideology itself was effective at building a strong fanatical base, the true influence lay in the party’s mass persuasion techniques.

(Photo Credit: Bundesarchive)

Well before the Nazis came to power, they already mirrored the institutions and organization of a state in their party. The Nazis effectively developed a state within a state, different party officials were assigned as ministers to different aspects of the party such as media, finances, and most importantly of all the paramilitary wings. Taking inspiration from Mussolini and his Blackshirts, the Nazis developed two parallel paramilitary organizations. Henrich Himmler was the leader of the Schutzstaffel or the SS, which was Hitler’s personal bodyguard unit composed of the most loyal and fanatical Nazis. They were so devoted to Hitler’s cult of personality that they were willing to give their life for him. For example, during Hitler's doomed Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, in defiance of the Weimer Republic, the Nazis arm in arm with Hitler marched headfirst into gunfire. “...[A]s they head towards the police blockade, his (Hitler’s) comrade is shot dead and pulls Hitler with him to the ground. Hitler’s armed bodyguard throws himself in front of the Fuher, taking eleven bullets to the chest, dying instantly.” (Olson & Hartvig, 2018). The other, much larger paramilitary organization was the Sturmabteilung, SA. Its leader was former First World War imperial army Captain Ernst Röhm. Röhm instilled military discipline, training, and a fanatical social revolutionary mindset into the SA making it a formidable force. The SA was similar to Mussolini’s Blackshirts, as they carried out the violent will of the party. They were known as the Brownshirts and violently suppressed anyone that opposed the Nazis. In Weimar Germany, it was a common sight to see Brownshirt thugs openly beating and even shooting at their communist foes in the streets. By the time the Nazis came to power in 1933, instead of the German public feeling fear from the brutal SA, they instead felt a sense of stability. At this point, the German public was subjected to well over a decade of revolutionary violence, when the Nazis came to power and gained a monopoly on violence a sense of order appeared to be re-established. The German people were so desensitized to violence that they came to accept it as a trade-off for stability.

In addition to being the leader of the SA, Röhm also frequently wrote for the Nazi party’s official newspaper Völkischer Beobachter. The Nazis greatly understood the importance of media and well before they took power they had multiple journals, newspapers, and publications spreading their ideology. At the forefront of the Nazi propaganda effort was the future Reich Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels. Goebbels made sure to insert Nazi ideology into all forms of communication and meticulously crafted coded language. Goebbels's Nazi language was based on the pervasive themes of exaggeration, victimhood, and racial unity. He was one of the first people in the world to use heavily sanitized doublespeak, which is the act of carefully choosing words to distort or obscure their true meaning. For example, Judeo-Bolshevism, International Finance, Blut und Boden (Blood and Soil), Gleichschaltung (Coordination), The Jewish Question, and Final Victory. These terms subtly hid the Nazis' true intentions. They paired the idea of communism with Jews so that they could target and group their opponents into one category. The Nazis used doublespeak as a way to soften their rhetoric to maintain public support while maintaining the narrative. “Through clever and constant application of propaganda, people can be made to see paradise as hell, and also the other way round, to consider the most wretched life as paradise.” (Klemperer, 1970). Euphemisms like Gleichschaltung deflected suspicion and outrage, the Nazis were not brutally suppressing their opponents and centralizing state control; they were merely coordinating all sectors of the state towards a stabilization operation.

The use of doublespeak paired with a constant stream of propaganda enabled most Germans to succumb to the Nazi ideology willfully or unknowingly. Goebbels paired terms like vermin and Untermenschen (sub-humans) with imagery of Jews. Due to mental heuristics such as the availability heuristic, the German people began to associate Jews with filth and inferiority. When the Jews became dehumanized, the German people were less likely to object to the gradual mistreatment and eventual extermination of them. Goebbels employed this tactic to other concepts core to the Nazi ideology. For example, the red, white, and black swastika flag was seen throughout Germany. The German people began to associate the swastika with feelings of pride, strength, and unity. “Vienna was scarcely recognizable this morning. Swastika flags flying from nearly every house. Where did they get them so fast?” (Shirer, 2015). Another practice that Goebbels heavily relied upon was gaslighting. Gaslighting is “ (the act of manipulating) another person into doubting their perceptions, experiences, or understanding of events.” (American Psychological Association, 2023). During the interwar years, Nazi Germany was hell-bent on militarization and expansionism. However, Hitler and Goebbels espoused rhetoric of peace and victimhood. They lied to the German people to convince them that they were the ones being oppressed and in need of liberation.

(Photo Credit: Keystone / Getty Images)

The power of imagery and symbolism was respected by the Nazis. Hitler was an avid film viewer and understood the value that film could have in spreading Nazi propaganda. Similar to Mussolini, Hitler would try to co-op already famous Hollywood actors into the German film scene to pair Nazism with the superstars of the day. “UFA will continue to produce entertainment films, with the slight difference that they are now pro-Nazi and work as subtle, invasive tools to spread the ideology of the party. In the 1930s UFA will produce and distribute in Germany, France, Belgium, and the United States, so that stars from the whole world, either wittingly or unwittingly, would now work for the Nazis to promote their cause, and we’re talking serious paycheck stars like Hans Albers, Zarah Leander, and Valentino’s last lover, Pola Negri.” (Olson & Kapteijns, 2019). However, unlike the Soviet Union or Mussolini’s Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany would take things a step further. They would not just repurpose newsreels, or subtly inject their ideology into film, but create entire films from the ground up with the sole purpose of spreading propaganda. The most infamous example of this was the film genius, Leni Riefenstahl. Films such as Olympia, Der Sieg des Glaubens, and Triumph des Willens would propel her and by extension the Nazis to international fame. She combined documentary-style filming with unprecedented symbolism and emotional appeals. Her filming techniques were so innovative and ahead of their time that directors of films such as Star Wars and 2001: A Space Odyssey would use her techniques. Art was another form of media that was hijacked by the Nazis to be used as a vehicle for their propaganda.

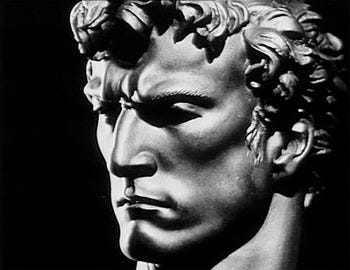

Arguably one of the most influential artists of Nazi Germany was Arno Breker. Breker embraced some of the ideals that were key to the Nazi movement such as romanticism and neoclassicalism. Breker’s sculptors took heavy influence from Renaissance artists like Michelangelo. His statues were extremely detailed and powerful in their symbolism. Breker’s aesthetic revolved around militaristic heroism. His statues represented Germanic warriors of the past and conveyed feelings of power, strength, and anger. He was careful to craft his statues in a way to be timeless so that they would not appear outright to be symbolic of Nazi Germany. Top Nazi officials like Hitler and Minister of Armaments and War Production, Albert Speer admired Breker’s works. They were displayed throughout Nazi Germany, invoking emotions harking back to the almost mythical romanticized past of the Germanic people, such as their victory over the Romans in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. His statues were used by the Nazis to demonstrate the exemplary nature of the Germanic people. Besides imagery such as art and film, another mode of media was paramount to reaching the minds of the German public; the radio.

(Photo Credit: Cambridge University Press)

One of the first acts that the Nazis did when they came to power was to implement total censorship and near-draconian rules on the media. State-run radio broadcasters would be the only ones permitted to be heard throughout Germany. If a German was caught listening to a foreign news broadcaster such as the BBC, they could be arrested by the Nazi secret police, the Gestapo. The Gestapo had secret radio intercept stations throughout Germany, silently listening for radio broadcasts and transmissions. Another important program was the Volksempfänger or the People’s Receiver. “They (the Nazis) will soon launch the Volksempfänger, the People's Radio Receivers so the party will have a loudspeaker in every home. Already after a few weeks, the Nazi Party has a firm grip on the German news cycles and the news is an endless stream of misinformation with a steady drip of repeated propaganda.” (Olson & Deinhard, 2019). The entirety of the Nazi propaganda machine would come together like an orchestra to perform a symphony of disinformation in the summer of 1939, on the eve of the Nazi invasion of Poland.

On every single People’s Radio Receiver in homes throughout Germany, the Nazi propaganda machine made a concerted effort to gaslight the German public. “In August 1939 German radio will broadcast endless loops of fake news claiming that the Poles are provoking German sovereignty at the borders, murdering ethnic Germans in Danzig and Poland, and must be stopped at any cost.” (Olson, 2020). German newspapers report on wildly false rumors that the Polish military was building up on the borders of Germany poised to attack. Faced with the threat of an imminent German invasion, the Poles began to mobilize and build up defenses. In response, the German media turned this around and in a frenzy whip up fears in the German public that the rumors were a reality. The situation became tense and all it required was one match for the whole thing to go up into flames. This match would be lit by the SS. “At 2000 hours in Hotel Haus Oberschlesien in the small town of Gleiwitz on the German-Polish border, German SS-Sturmbannführer Alfred Naujocks gets a phone call…He and his accomplices take over the Gleiwitz radio relay station and repeatedly broadcast the following message in German and Polish: “Achtung! Achtung! This is Gleiwitz. The station is under Polish control […] The hour of freedom has arrived!” For four minutes they then call for Polish militants to rise up against Germany and end with “Long live Poland!“ And with these lies, these cynical words, the German war machinery is finally set in motion.”(Olson, 2020). One of the darkest chapters in human history would begin with a lie. For the six years that the Nazis were in power up to this point, they fed the German people an endless flood of lies to prepare them for this very moment. For the next six years of war, the German public would continue to be fed lies, preparing them to sacrifice everything for the genocidal will of their Fuher.

The Second World War showed us the true horror and influential power of crowd psychology in the hands of totalitarian regimes. On the Eastern front, the two colossal ideologically opposed totalitarian titans; the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany along with her allies waged a brutal war of annihilation. Completely consumed by propaganda the soldiers of both sides learned to view their enemies as something not human. Radicalized, both sides would slog it out in the meatgrinder. Millions of soldiers perished in this new industrial modern war. The Germans believing they were on a great crusade against Judeo-Bolshevism sought the destruction of their mortal enemy for the promise of lebensraum (German expansionism). In the name of this supposed righteous cause, the Germans would slaughter, rape, and pillage millions of civilians and prisoners of war. In return, when the Soviet Red Army swept across the Eastern front to the doorstep of Berlin, in retribution they would do the same; raping looting, and murdering their fascist foes. Upon the destruction of Nazi Germany, instead of being liberated the people of Eastern Europe would be consumed by the Iron Curtain under the boot of Stalin. Replacing one totalitarian regime with another, the communist propaganda machine now churned out propaganda demonizing the imperialistic west beginning the Cold War.

(Photo Credit: Georgy Zelma/Waralbum.ru)

Ever since the publication of theories of crowd psychology, popularized by Le Bon and others, we have lived in the era of mass manipulation. Like the pioneering propagandists of the 1920s, today modern-day propagandists adapt to ever-evolving technological advances. However, despite these advances, the core principles of crowd psychology remain. Many of yesterday’s tactics are still being used today. The works of theorists such as Gabriel Tarde, Gustave Le Bon, and Edward Bernays are just as relevant, if not even more today. Whether it be domineering corporations, authoritarian regimes, or even our government, we must remain vigilant and aware. We have seen when mass manipulation tactics are utilized by totalitarian regimes; such as the Nazis, The Soviets, or The Fascists the people become just another tool of the state easily thrown away with our highly valued ideals including liberal democracy. While we would like to think that we are different than the people of the past, history has shown us that is not the case. Despite having written his most prominent work almost five hundred years ago, Machiavelli’s words still hold today. However, one thing is different compared to the past, we know the history. In the spirit of the original psychologists who penned their words over a century ago, let us educate ourselves so that when others wish to do harm with their words, we are prepared to fight back. We must arm ourselves not with weapons but with critical thinking skills to better adapt to the ever-changing information environment we find ourselves in today. We must not grow apathetic to the actions of others and allow them to condition us to their will lest we find ourselves saying the same words as the Italians once did over one hundred years ago “ I do not give a damn.” In the legendary words of George Santayana “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Let us not forget the past.

References

American Psychological Association. (2018, April 19). APA Dictionary of Psychology Definition Of Crowd Psychology. American Psychological Association. https://dictionary.apa.org/crowd-psychology

American Psychological Association. (2023, November 15). APA Dictionary of Psychology Definition Of Gaslight. American Psychological Association. https://dictionary.apa.org/gaslight

American Psychological Association. (2018, April 19). APA Dictionary of Psychology Definition Of Propaganda. American Psychological Association. https://dictionary.apa.org/propaganda

Bernays, E. L. (1928). Propaganda. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.275553/page/n47/mode/2up

Conquest, R. (1998, April 30). Inside Stalin’s darkroom. Hoover Institution. https://www.hoover.org/research/inside-stalins-darkroom

Creel, G. (1920). How we advertised America; the first telling of the amazing story of the Committee on Public Information that carried the Gospel of Americanism to every corner of the globe: Creel, George, 1876-1953. [from old catalog]: Free Download, Borrow, and streaming. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/howweadvertameri00creerich/page/3/mode/1up

Dome, C. (n.d.). A Timid Flock: Investigating Propaganda Under Stalin. Evergreen State College. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://jsis.washington.edu/ellisoncenter/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2016/05/dome_REECASNW.pdf

Gentile, G. (2002). Origins and doctrine of fascism. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/download/OriginsAndDoctrineOfFascismGiovanniGentile/Origins%20and%20Doctrine%20of%20Fascism%20-%20Giovanni%20Gentile.pdf

Hitler, A. (1939, February). Mein Kampf. Great War. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://greatwar.nl/books/meinkampf/meinkampf.pdf

Klemperer, V. (1970, January 1). The language of the Third Reich: LTI, Lingua Tertii imperii: A philologist’s notebook. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/languageofthirdr0000klem/page/n7/mode/2up

Kraut. (2018, September 12). Yesterday's Tactics on Modern Media. YouTube.

Le Bon, G. (1996, February 1). The Crowd: A Study Of The Popular Mind. The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Crowd. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/445/pg445-images.html

Machiavelli, N. (1998, March). The Prince. The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Prince, by Nicolo Machiavelli. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1232/1232-h/1232-h.htm#chap00

MacKay, C. (2005, February 5). Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions And The Madness Of Crowds. The Project Gutenberg eBook of Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, by Charles Mackay. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/24518/24518-h/24518-h.htm

McCutcheon, J. M. (n.d.). Torches of Freedom Campaign. Omeka RSS. https://omeka.uottawa.ca/jmccutcheon/exhibits/show/american-women-in-tobacco-adve/torches-of-freedom-campaign

Merrill, T. (2017, January 10). Tarde, Gabriel (1843–1904). Tarde, Gabriel (1843–1904) - Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism. https://www.rem.routledge.com/articles/tarde-gabriel-1843-1904#:~:text=New%20ideas%20spread%20via%20imitation,reinforce%20or%20replace%20customary%20ones.

Mussolini, B. (1922, October 24). DISCORSO DEL 24 Ottobre 1922. Discorso del 24-10-1922. http://www.mussolinibenito.it/discorsodel24_10_1922.htm

Mussolini, B. (1932). The doctrine of fascism. https://sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda/2B-HUM/Readings/The-Doctrine-of-Fascism.pdf

Mussolini, B. (1970, January 1). My autobiography: Benito Mussolini. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/MyAutobiography/MyAutobiography/page/n27/mode/2up

Olson, S. (2020, April 8). The True Story of How WW2 Began | Between 2 Wars I 1939 part 3 of 3 I season finale. YouTube.

Olson, S., & Deinhard, A. (2019, October 31). Why “All Germans Were Nazis” - How Hitler Created the 3rd Reich | BETWEEN 2 WARS I 1934 Part 1 of 4. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLrG5J-K5AYAU1R-HeWSfY2D1jy_sEssNG

Olson, S., & Hartvig, R. V. (2018, November 10). Hitler’s Beer Hall disaster I between 2 wars I 1923 part 1 of 1. YouTube.

Olson, S., & Kapteijns, W. (2019, March 13). How Hollywood Helped Hitler | Between 2 Wars | 1926 part 2 of 3. YouTube.

Sklar, R. (2024, March 5). History Of Film: The Soviet Union. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/art/history-of-the-motion-picture/The-Soviet-Union

Shrier, W. L. (2015). Berlin diary the Journal of a foreign correspondent 1934 1941. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.178047

Sorel, G. (1999). Reflections on Violence. Cambridge Texts In The History Of Political Thought. https://files.libcom.org/files/Sorel-Reflections-on-Violence-ed-Jennings.pdf

Soviet Propaganda Under Lenin. GCSE Modern World History. (2009). https://www.johndclare.net/Russ6_SovietPropaganda.htm

Tarde, G. (1903, September). The Laws Of Imitation. Internet Archive. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://ia800208.us.archive.org/4/items/lawsofimitation0

Tolchinsky, A. (2020, November 16). CDC Foundation Launches Crush COVID-19 Campaign To Meet Urgent Needs Caused by Pandemic. CDC Foundation. https://www.cdcfoundation.org/pr/2020/crush-covid-campaign

Trotter, W. (2016, November 5). Instincts of the herd in peace and war. Instincts of the Herd in Peace and War, by W. Trotter, A Project Gutenberg eBook. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/53453/53453-h/53453-h.htm