Beyond Cuba: China's Growing Intelligence and Economic Footprint in Latin America

We analyze China's expanding intelligence operations and influence across the Americas, examining key activities such as the SIGINT base in Cuba, dual-use infrastructure projects, and more.

Now especially more than ever we are witnessing a growing geopolitical rivalry between the United States of America and the People's Republic of China. Nowhere is this struggle more pronounced than in the Indo-Pacific as demonstrated by a surge in military, economic, and diplomatic activity1. Although direct military conflict has not erupted, a war is already underway through gray zone operations, where both nations engage in covert actions and strategic maneuvers just below the threshold of open conflict2 This growing conflict mirrors aspects of the Cold War, where intelligence gathering and counterintelligence operations were essential components of statecraft and strategic geopolitical maneuvering. The Indo-Pacific region, and specifically Taiwan, has become a focal point for U.S. intelligence activities, as Washington seeks to monitor China’s military expansion and assertiveness. The rivalry between the two global powers is not limited to military power; it involves cyber, economic, and signals intelligence (SIGINT) domains, as both nations seek to maintain an edge in technology and intelligence. Like a game of chess, China seeks to counter U.S. influence, not only in the Indo-Pacific but also far beyond—throughout the entirety of the Americas.

Though geographically distant from the Indo-Pacific, Chinese intelligence activities in Latin America are part of a broader strategy to gather information on U.S. military and economic operations. By embedding itself in the Western Hemisphere, Beijing is expanding its intelligence capabilities and supplanting U.S. influence in Latin America; taking the fight right to the U.S.’s backyard. However, unlike the U.S.'s Cold War foe, the Soviet Union, China is not fomenting revolution in Latin America. The Chinese approach is more subtle; focused on building influence through economic engagement, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and cultural exchanges, which gives China leverage over regional governments.3 As a rising power, China seeks to create a new order by presenting itself as a more attractive alternative and leveraging its economic might.

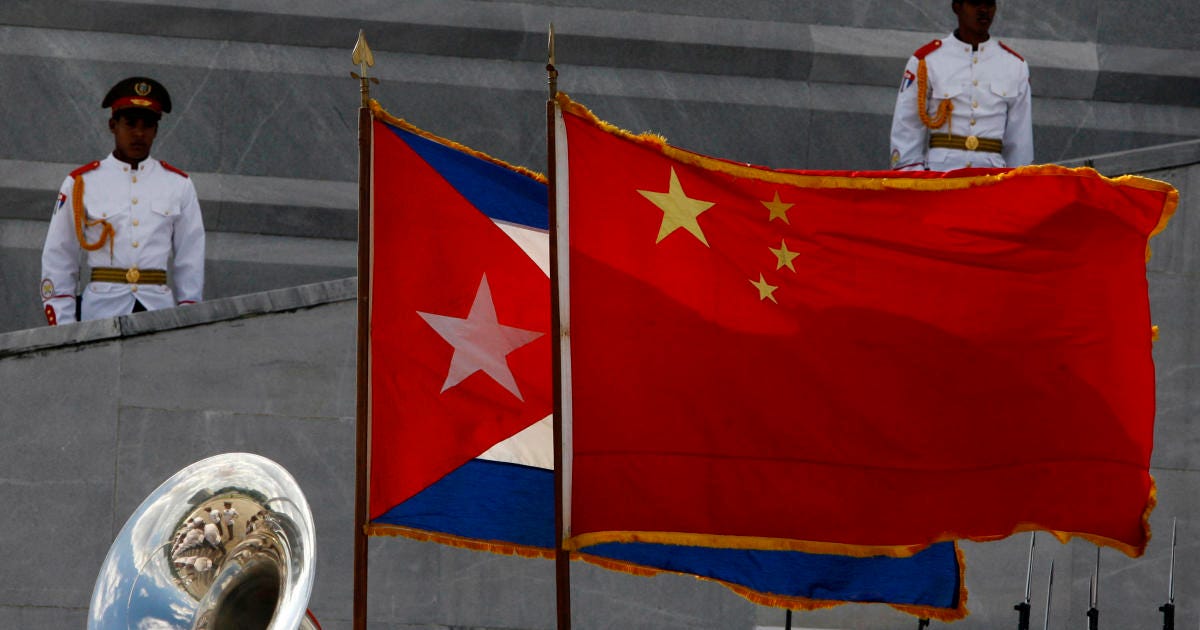

(Photo Credit: Jam Sta Rosa | AFP)

Ever since the Biden administration revealed that it knew that China has access to multiple spy bases in Cuba4, there has been a whirlwind of speculation and discussion centered on this topic. Multiple news articles and reports have discussed a Chinese signals intelligence (SIGINT) base near Santiago de Cuba, believed to be part of China’s growing intelligence operations in the Western Hemisphere. According to satellite imagery analysis by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), the base, still under construction since 2021, features a circularly disposed antenna array (CDAA), which is designed to intercept high-frequency signals.5 This type of equipment allows analysts to determine the origin and direction of communications, potentially enabling the monitoring of U.S. air and naval activity in the region. Given its proximity—just 50 miles from the U.S. military base in Guantanamo Bay—the base could serve as a significant tool in China’s efforts to gather intelligence on U.S. military operations. In addition to Guantanamo Bay, the base is also well within range of a plethora of U.S. military installations located in the southern U.S. most notably USSOUTHCOM headquarters based out of Doral, Florida.

(Photo Credit: CSIS)

However, despite the media attention surrounding the base, its strategic significance may be overstated. The geographic location of Cuba, while close to U.S. military facilities, limits its direct relevance to China's broader goals in the Indo-Pacific. The base may enable the interception of communications or naval traffic in the Caribbean, but the intelligence gathered here is less likely to have immediate applications for China’s primary theater of operations, which remains focused on Asia, particularly Taiwan and the South China Sea. The base in Cuba is more symbolic, signaling China's global reach rather than serving a critical operational need.

Moreover, the U.S. may view the base as a controlled opportunity to gather insights into Chinese intelligence techniques, known as Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs). By allowing limited Chinese espionage activity, the U.S. could gain valuable counterintelligence insights into China's operational methods, while managing the risk of significant data breaches. The U.S. may also use the opportunity to deliberately leak false information to the Chinese to mislead them. Additionally, the Chinese presence in Cuba may also serve to de-escalate tensions by promoting transparency. By providing China with a less critical window of intelligence, the U.S. can show China that its military movements are not aggressively directed toward them, decreasing the risk of accidental escalation.

(Photo Credit: Gao Xiao Wen | Imagine China)

Another topic that is wildly misunderstood and overstated is the Chinese presence at the U.S. southern border with Mexico. Some fear that China is using the southern border to insert human intelligence (HUMINT) operators into the U.S., however, this is far from reality. China instead demonstrates its capacity for sophisticated infiltration through legal migration and the existing Chinese-American community. Recent incidents illustrate this trend: the discovery of a secret Chinese police station operating in plain sight in New York City6, the covert activities of Communist Party operatives to intimidate and surveil Chinese expatriates7, and the indictment of various individuals who allegedly committed espionage on behalf of China including a former aide to two New York governors8 and a former CIA officer9.

The U.S. Department of Justice has initiated a wave of prosecutions aimed at dismantling these covert networks, with federal prosecutors in New York’s Eastern District alone bringing at least a dozen cases against over 90 individuals in the past four years10. The risks associated with attempting to insert assets via the southern border are substantial; such actions would attract considerable scrutiny and could jeopardize their objectives. Additionally, it would be substantially more difficult for these operators to infiltrate high levels of government without a convincing cover story. The current Chinese approach allows for a more discreet integration of individuals who may have dual roles. In reality, the thousands of Chinese individuals crossing the southern border are genuinely seeking better lives, fleeing difficult circumstances in China11. Understanding the genuine intentions of these migrants crossing the southern border is vital, as it contrasts sharply with China's more organized and sophisticated intelligence operations in Latin America.

China's intelligence operations in Latin America extend beyond Cuba, with one of the most significant activities being a satellite intelligence (SATINT) facility in Argentina. Located in the remote Patagonian desert, this 500-acre base features a powerful 16-story, steerable parabolic antenna operated by the China Satellite Launch and Tracking Control General (CLTC), a unit of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)12. The facility is designed for telemetry, tracking, and command of various Chinese space missions, making it a critical listening post for global intelligence collection. The remote location allows for minimal oversight from the Argentine government, providing China with a strategic advantage in monitoring telecommunications and reconnaissance activities in the region, particularly concerning U.S. satellite assets over the Western Hemisphere.

(Photo Credit: Agustin Marcarian | Reuters)

To effectively operate satellites on the opposite side of the Earth, China requires ground stations capable of tracking and communicating with its satellites within the Western Hemisphere. The facility in Argentina serves this purpose by providing a satellite station in the Southern Hemisphere, enabling China to monitor and control its space assets effectively. In addition, Cuba offers China access to ground stations in the Northern Hemisphere, creating a comprehensive network. This dual-access strategy enhances China's ability to conduct surveillance and intelligence operations across the Americas, solidifying its foothold in the region. Establishing these ground stations is not merely a logistical necessity; it aligns with China's broader intelligence objectives. By creating a network of facilities that span both hemispheres, China enhances its capacity for space-based data collection, ensuring that it can monitor and respond to developments in real-time.

Chinese-controlled ports in Latin America, particularly in Panama13 and Peru14, serve dual purposes by operating as both commercial hubs and intelligence-gathering outposts. These ports are strategically located near key maritime chokepoints, including the Panama Canal and the Strait of Magellan15, which are critical for global shipping. While officially focused on trade, these ports allow China to collect intelligence on Western and U.S. naval movements. By monitoring shipping routes and U.S. military logistics in the region, China gains crucial insights into maritime security dynamics, enhancing its strategic capabilities and influence in the Western Hemisphere. In addition to monitoring naval movements, these ports provide China with cyber access to critical shipping and logistical information. By integrating sophisticated digital systems into port operations, China can potentially intercept data on U.S. and Western port operations, including the type of ships, cargo, and routes used. This cyber aspect enables China to collect intelligence through digital surveillance of shipping manifests, container tracking, and communication networks.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has further facilitated the expansion of Huawei and other Chinese firms into Latin American telecommunications, providing backdoor access to critical infrastructure and sensitive data flows across the region. Huawei, a dominant player in building 5G networks and data systems, raises significant concerns about potential exploitation for intelligence purposes. Additionally, Chinese involvement in AI-based security projects, such as facial recognition systems, presents vulnerabilities that could enable espionage. These systems, often deployed for surveillance and cybersecurity, could be leveraged for intelligence gathering on governments, corporations, and U.S. allies, increasing fears of digital dominance and cyber espionage throughout Latin America.

Chinese influence operations in Latin America focus primarily on the control and management of Chinese emigrant communities, particularly through the establishment of "Chinese Overseas Police Service Centers." Recent investigations16 reveal that local Public Security authorities have set up at least 102 of these centers in 53 countries, including Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Panama, Cuba, and Venezuela facilitating "persuasion to return" operations targeting Chinese emigrants. These centers, part of a broader network managed by the Chinese Communist Party, engage in tactics designed to intimidate individuals into returning to China for persecution. The CCP’s goal is to create an environment of fear that stifles open dialogue and dissent among the diaspora. The presence of these centers not only undermines the rights of targeted individuals but also poses a significant challenge to the sovereignty of Latin American countries.

China's approach to economic coercion in Latin America is a multifaceted strategy aimed at enhancing its political leverage in the region, particularly through trade, investment, and infrastructure development. The rapid expansion of trade relations—growing from $12 billion in 2000 to $315 billion by 2020—positions China as South America's largest trading partner17. This economic interdependence creates a scenario where Latin American countries may feel compelled to align their policies with Chinese interests to maintain favorable trade relations. China employs mechanisms such as tariffs and import restrictions to influence local economies. Countries opposing Chinese interests risk facing trade penalties that can force compliance. Through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China further expands its influence by offering financial incentives for infrastructure projects. Investments in roads, ports, and energy sectors strengthen economic ties and increase dependence on Chinese technology and capital, making it harder for countries to resist Beijing's influence. This strategy can lead to debt dependency, where nations may find themselves unable to oppose Chinese demands due to financial vulnerability, thereby facilitating a form of economic coercion. As a result of these tactics, nations like El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua have severed ties with Taiwan18, demonstrating how China’s strategic maneuvering in Latin America influences its broader geopolitical interests.

(Photo Credit: Getty Images)

China's broader aims in Latin America encompass not only the increase of its influence within the Western Hemisphere but also the suppression of dissent within diaspora communities and the pursuit of economic and technical advantages through cyber and corporate espionage. By actively engaging with Latin American nations, China seeks to cultivate favorable relationships that align with its political objectives, particularly its One-China policy. Additionally, Chinese initiatives target diaspora communities, aiming to silence dissent and build narratives that favor Beijing. This involves influencing local opinions and leveraging social media to promote pro-China sentiments, thereby reducing opposition to Chinese policies and actions.

In terms of economic dominance, China employs strategic tactics to weaken local competition through aggressive buyouts and investments in key sectors. Chinese state-owned enterprises and corporations leverage their financial resources to acquire promising local businesses, effectively monopolizing markets and consolidating their presence. This approach not only undermines local industries but also establishes a network of Chinese-controlled economic interests, enhancing Beijing's leverage over regional economies. Furthermore, China is notorious for engaging in corporate espionage, forcefully acquiring technical data, and reverse engineering products and technological developments. This practice allows Chinese firms to rapidly advance their capabilities while diminishing the competitive edge of local and foreign companies operating in Latin America.

Chinese intelligence operations in Latin America fit into the broader picture of U.S.-China geopolitical competition. As China expands its influence, it directly challenges U.S. strategic interests, particularly in a region historically considered within the American sphere of influence. China's growing influence could erode support for U.S. policies in Latin America, weaken alliances, and shift regional alignment toward Beijing, making it harder for the U.S. to secure cooperation on transnational issues such as trade, climate change, security, and migration especially.

(Photo Credit: Javier Galeano | AP)

As intelligence competition intensifies, the future trajectory of U.S.-China relations in Latin America is poised for significant shifts. The U.S. has already initiated the adaptation of several strategies to counterbalance China's growing influence, including enhancing bilateral trade agreements, increasing development assistance, and increasing military/security partnership engagements. Strengthening diplomatic ties with countries that are favorable to the U.S. will also be vital to combining Chinese influence in the region. China's influence in Latin America often leads to unequal partnerships, where the region's economies become reliant on Chinese investments while Beijing reaps the benefits, especially in terms of resource extraction. China's support for authoritarian regimes like Maduro's in Venezuela and its willingness to bypass regulations promote corruption and undermine democratic institutions. By fostering dependency and economic domination, China prioritizes its strategic interests over the long-term well-being of Latin American nations, making its involvement more exploitative than beneficial for the region. This is why the U.S. must push back against China's growing presence.

Sino Talk’s Analysis:

China's intelligence activities in Latin America extend beyond its Signals Intelligence base in Cuba and its 11 satellite tracking ground stations throughout the region, but also include companies and other entities connected to the People's Liberation Army (PLA) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The most notable example of this is how several PLA-linked firms control or are heavily involved in port projects at various sections along the Panama Canal. China could use these companies to collect intelligence on U.S. Navy ships that move through the canal or the ports located at the canal’s Atlantic and Pacific ends. However, this concept could also be applied to other port and infrastructure projects that have Chinese involvement, such as the Chancay port in Peru, hospitals in Colombia, and phone networks in Chile. These projects would enable China to not only collect intelligence on the U.S. but also other countries including the nations where they are built. Furthermore, China could use these projects to compel other countries to enter into secret intelligence sharing or basing agreements, which would allow the country to use the projects as intelligence collection sites.

The 2017 National Intelligence Law (NIL) would force Chinese companies operating in South America to assist intelligence agencies, such as the Ministry of State Security (MSS). The MSS and other agencies could use the law to force firms to comply with requests to provide information about the projects. The law can also force companies to assist intelligence agencies with intelligence operations in South America through a variety of means. These means can range from granting access to the buildings owned by the companies to requiring the intelligence agencies to use the companies as cover for agency personnel. The MSS and other organizations could use the 2014 Counterintelligence Law (CIL) to force Chinese companies to provide them with information if they deem it necessary for counterintelligence operations. Furthermore, like the NIL, Chinese intelligence companies could use the CIL to force organizations to assist them in counterintelligence operations, including forcing businesses to grant them access to their facilities.

Joe Cash, “China Holds Military Drills in South China Sea after Talks with U.S. | Reuters,” Reuters, September 28, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/china-holds-military-drills-south-china-sea-after-talks-with-us-2024-09-28/

Taiwan: Defense and Military Issues - CRS reports, August 15, 2024, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12481.

Pavel K. Baev Aslı Aydıntaşbaş et al., “Countering China and Russia’s Asymmetric Activity in Latin America,” Brookings, July 18, 2023, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/countering-china-and-russias-asymmetric-activity-in-latin-america/.

Gordon Lubold and Warren P. Strobel, “White House Says China Has Had Cuba Spy Base since at Least 2019 - WSJ,” The Wall Street Journal , June 11, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/white-house-says-china-has-had-cuba-spy-base-since-at-least-2019-42145596.

Matthew P. Funaiole et al., “Secret Signals: Decoding China’s Intelligence Activities in Cuba,” Center For Strategic Studies CSIS, July 1, 2024, https://features.csis.org/hiddenreach/china-cuba-spy-sigint/.

Larry Neumeister and Eric Tucker, “Secret Chinese Police Station in New York Leads to Arrests,” AP News, April 19, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/chinese-government-justice-department-new-york-police-transnational-repression-05624126f8e6cb00cf9ae3cb01767fa1.

Jennifer Peltz, “3 Men Convicted in US Trial That Scrutinized China’s ‘Operation Fox Hunt’ Repatriation Campaign,” AP News, June 20, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/china-repatriation-operation-fox-hunt-trial-new-york-01f96f6952e772efb5814c12316922dc.

Philip Marcelo, Eric Tucker, and Didi Tang, “The Arrest of a Former Aide to NY Governors Highlights Efforts to Root out Chinese Agents in the US,” AP News, September 5, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/china-foreign-agents-new-york-governor-hochul-2930f274c621ae3bc3dacc8635a468eb.

Christopher Burges, “Recent Arrests Uncover Depth of Chinese Espionage,” ClearanceJobs, September 12, 2024, https://news.clearancejobs.com/2024/08/17/recent-arrests-uncover-depth-of-chinese-espionage/.

“Queens Resident Convicted of Acting as a Covert Chinese Agent,” U.S. Attorney’s Office, Eastern District of New York, August 6, 2024, https://www.justice.gov/usao-edny/pr/queens-resident-convicted-acting-covert-chinese-agent.

James Palmer, “Why Are More Chinese Migrants Arriving at the U.S. Southern Border?,” Foreign Policy, May 7, 2024, https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/05/07/china-us-southern-border-migration-darien-gap/.

Victoria Vogrincic, “China’s Heightened Space Presence in the Heart of Argentina’s Patagonian Desert,” China Focus, November 19, 2020, https://chinafocus.ucsd.edu/2020/11/19/chinas-heightened-space-presence-in-the-heart-of-argentinas-patagonian-desert/.

John Grady, “Chinese Investment near Panama Canal, Strait of Magellan Major Concern for U.S. Southern Command,” USNI News, March 24, 2022, https://news.usni.org/2022/03/24/chinese-investment-near-panama-canal-strait-of-magellan-major-concern-for-u-s-southern-command.

Leland Lazarus, “A China-Funded Port in South America Could Threaten U.S. National Security,” China US Focus, July 17, 2024, https://www.chinausfocus.com/finance-economy/a-china-funded-port-in-south-america-could-threaten-us-national-security.

See footnote 13

“Patrol and Persuade - a Follow up on 110 Overseas Investigation,” Safeguard Defenders, December 5, 2022, https://safeguarddefenders.com/en/blog/patrol-and-persuade-follow-110-overseas-investigation.

Evan L. Pettus, “The Expanding Leverage of the People’s Republic of China in Latin America: Implications for US National Security and Global Order,” Air Combat Command, October 5, 2023, https://www.acc.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/3550020/the-expanding-leverage-of-the-peoples-republic-of-china-in-latin-america-implic/.

Ana Rosa Quintana-Lovett, “Latin America, China and Taiwan,” GIS Reports, September 16, 2024, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/latin-america-taiwan/.

Additional References:

ANNUAL THREAT ASSESSMENT OF THE U.S. INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY. (2023, February 6). Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Retrieved September 28, 2024, from https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2023-Unclassified-Report.pdf

Are China and Russia on the cyber offensive in Latin America and the Caribbean? (n.d.). New America. https://www.newamerica.org/cybersecurity-initiative/reports/russia-china-cyber-offensive-latam-caribbean/chinese-and-russian-use-of-cyber-capabilities-in-latin-america-and-the-caribbean/

Frederick, B., Gunness, K., Lin, B., Cooper, C. A., III, Rooney, B., Benkowski, J., Chandler, N., Garafola, C. L., Hornung, J. W., Mueller, K. P., Orner, P., Heath, T. R., Curriden, C., & Ellinger, E. (2023, January 12). Managing the escalation risks of U.S. military activities in the Indo-Pacific. RAND. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RBA972-1.html

Fu, D., & Dirks, E. (2024, February 16). China’s overseas police stations: An imminent security threat? Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/chinas-overseas-police-stations-an-imminent-security-threat/

Harding, A. (n.d.). China’s plans for Latin America go beyond spying from Cuba | The Heritage Foundation. The Heritage Foundation. https://www.heritage.org/asia/commentary/chinas-plans-latin-america-go-beyond-spying-cuba

Martina, M. (2024, July 3). New Cuban radar site near US military base could aid China spying, think tank says. Reuters. Retrieved September 28, 2024, from https://www.reuters.com/world/new-cuban-radar-site-near-us-military-base-could-aid-china-spying-think-tank-2024-07-02/

Roy, D. (2023, June 15). China’s growing influence in Latin America. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/china-influence-latin-america-argentina-brazil-venezuela-security-energy-bri#chapter-title-0-7

STARTLING STATS FACTSHEET: Encounters of Chinese nationals surpass all fiscal year 2023 at the Southwest Border – Committee on Homeland Security. (2024, April 18). https://homeland.house.gov/2024/04/18/startling-stats-factsheet-encounters-of-chinese-nationals-surpass-all-fiscal-year-2023-at-the-southwest-border/

Task & Purpose. (2024, September 20). China’s spy base in Cuba needs to chill out [Video]. YouTube.

United States of America v. CHEN GUANG GONG,. (2024, February 5). U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved September 28, 2024, from https://www.justice.gov/opa/media/1337756/dl?inline